Sir Timothy O’Brien was not only a resident of Lohort but also was a local ‘character’. A man of exceptional sporting fame himself, he was connected with events and people of great national moment through the Parnell period and the early days of Irish national emergence. He was associated with Lohort for about forty years until 1917.

In the last quarter of the 19th century, Lohort was owned and occupied by a man called Sir Timothy O’Brien. Unusual for a resident of this latterly very English retreat, he was a Catholic. He inherited his knighthood from his grandfather. He inherited the castle and land from his father who had purchased it at the break-up of the Egmont/Perceval estates. His father was a prosperous Dublin publican, a younger son of Sir Lucius O’Brien of Dromoland, a nephew of William Smyth-O’Brien, the famous Irish Nationalist and liberal politician from County Clare, and close friend and confidante of the great Daniel O‘Connell. The family was a cadet branch of the extended Earls of Thomond and Inchequin whose less reputable roots led back to Morrogh O’Brien Lord Inchequin, ‘Morrogh of the Burnings’, well known to the people around Castlemagner for his victory over Lord Taaffe and Sir Alasdair McColla Ciotach McDonnell at Knocknanuss in 1647.

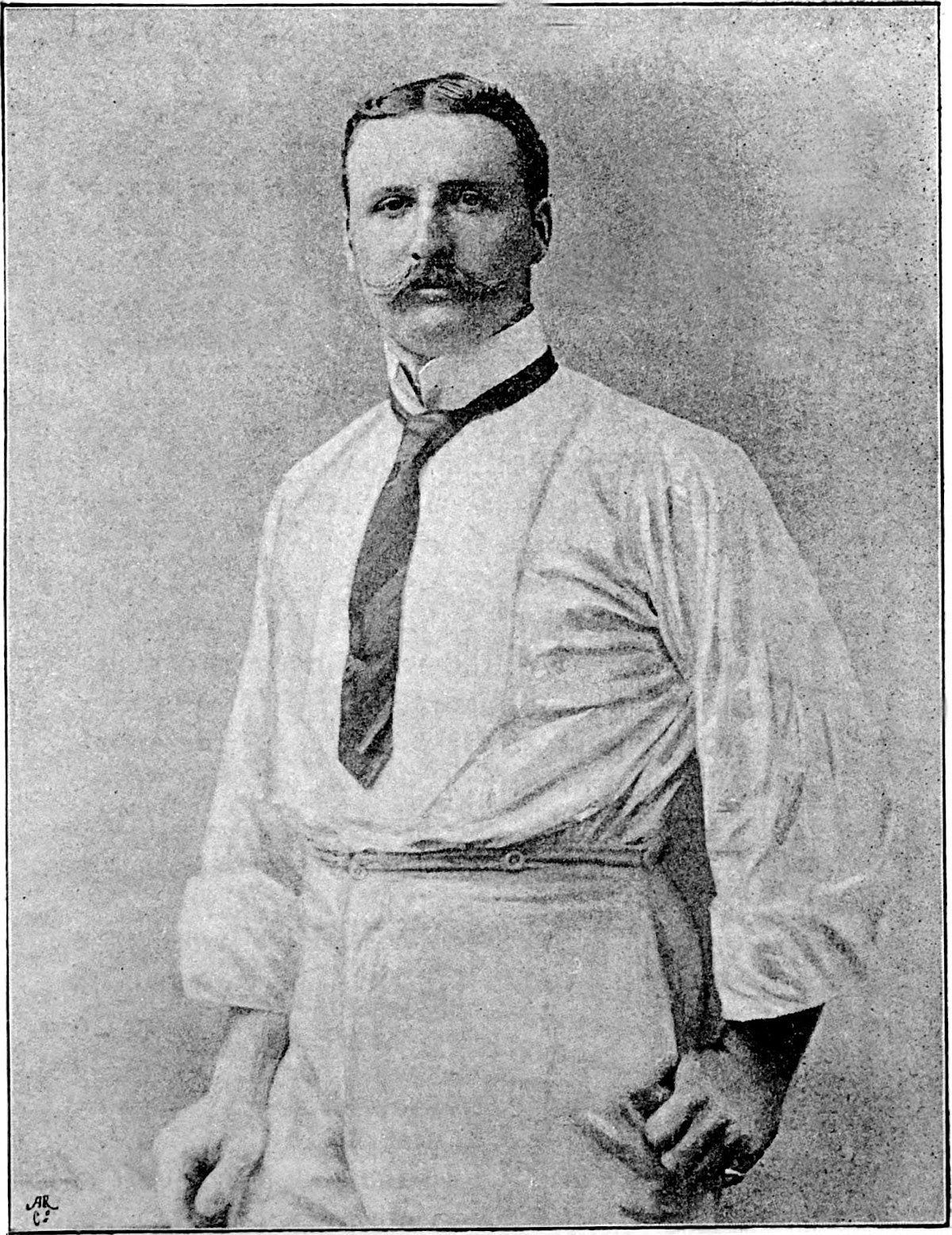

Sir Timothy’s youth was spent in Dublin and at leading public schools in Ireland and in England. Very much the Anglo-Irish gentleman of wealth and leisure, as a young man he moved in the top levels of Establishment society in Ireland and England and grew to excellence at various sports. An England international at Lawn Tennis and Cricket, his chief claim to sporting fame was as opening batsman with the England cricket team. He also played for Ireland and indeed had the unique distinction of representing both countries at international level. He organised and financed the setting up of the famous Lords cricket ground in London.

He was also a founding member of the Tennis Club attached to Wimbledon Cricket Club, latterly home of the famous Wimbledon Tennis Tournament.

In the mid-to-late 19th century in Ireland, most Big Houses and landlord estates, including Doneraile, Lohort, Castlecor and Ballygiblin in North Cork, sported a cricket team. Sir Timothy played with Lohort and the ambition of every local lad was to clean-bowl the famous batsman. A few succeeded, one was Alexander O’Callaghan, father of the late Billy Alex of this parish, who was groom to Sir John Wrixon-Becher and played on the Ballygiblin team. The local people got great satisfaction from Alex’s achievement !

Sir Timothy is also remembered for bringing the first ever motor car on to the stony roads of Castlemagner. The story goes that his fantastic machine emerged from the main gate of Lohort on a sunny August evening around 1890. He headed up through Cecilstown village, going towards Ballygiblin and Ballyhass in a cloud of smoke and dust, clattering and banging like a machine gun. A young lad from the village raced in front of the car, apparently being chased down by it. He waved a red flag on a pole and shouted ‘clear the way for his Lordship, clear the way!’. His progress sent cattle and horses racing in fright along the roadsides. Crowds of locals, convinced that ‘the soldiers are coming’ took off for Hartland’s Wood in Ballygiblin estate to hide for their lives.

Sir Timothy, like most of the Anglo-Irish gentry in North Cork, rode to hounds with the Duhallow Hunt. He was a noted horseman and point-to-pointer despite his lanky height of 6’4″. His membership of the Duhallow Hunt was to prove disastrous. In 1890 he bought a 17-hands thoroughbred hunter from Alexis Burke Roche of Assolus House, younger son of Lord Fermoy, for £100. The horse turned out to be broken-winded and Roche refused to buy it back. After a bitter exchange of solicitors’ letters, the two men chanced to come together at a meeting of the Duhallow Hunt at Springfort Hall on New Years Day 1891. Sir Timothy confronted Roche “You are a liar and a cheat and a swindler; you have lived by swindling for the past 20 years”. The two were separated with difficulty and Roche issued a writ for slander immediately.

The case was heard in the Circuit Court in Cork City in June 1891 and, because of the status and repute of Sir Timothy, it assumed countrywide interest with barristers of national status appearing for each side. After much-reported legal argument, the judge found in favour of Roche. He said that neither man was interested in money but wanted only to run the other man out of North Cork in disgrace. He held that such an objective was not in the spirit of the law. He awarded Roche 1 farthing damages but each party was to bear their own costs.

Roche, referred through throughout the case as Lord Fermoy, took his appeal to the Queen’s Bench in London and the case was heard in June 1892. Most of the Duhallow Hunt present at the confrontation in Springfort Hall were called to London as witnesses, along with numerous servants and character witnesses, all with full expenses paid. Sir Timothy’s chief witness was his own groom who had previously worked for Roche. The groom gave evidence that Roche was a regular swindler in horse dealing. Roche’s counsel was able to show that the groom had previously been employed by Roche but had been sacked for dishonesty and demolished the groom’s standing as a witness.

The hearing lasted 3 months and attracted international interest. The judge found for Roche. He re-iterated the comments of the Circuit Court judge and awarded Roche only £5 damages. However, he allowed Roche full costs and Sir Timothy had to bear all the costs of the two trials. The costs were huge and he more or less went broke paying them.

The case was famous for the ‘Irishisms’, that it threw up, viz:

Groom: ‘Lord Fermoy grabbed Sir Timothy’s bridle’.

Judge: ‘For legal accuracy, was it the horse’s bridle or Sir Timothy’s?

Groom: ‘The horse’s, my Lord; Sir Timothy was unbridled that day” (he shot his mouth off)

The case is still a standard text for students of the Law of Tort as related to Slander.

Sir Timothy was very much a Unionist British Establishment figure and his association with Lohort Castle ran through what were probably the most hectic events in Irish nationalist history. The latter days of his cricketing career coincided with the Land War and the bitter struggles between landlords and tenants that brought the Land Act of 1886. He was a partisan on the Landlord side, with a reputation at Lohort for being remote and unsympathetic towards his own tenants.

He was a Parnellite and took Parnell’s side in the political campaign that ended with the death of Parnell in 1891. When the Boer War broke out in South Africa in1899 he was active in promoting the jingoistic Establishment war propaganda and attempted to procure men and horses locally for the British Army. He had some limited success and 25 men from Cecilstown went with the Munster Horse to South Africa – never to return. But the bitter Land War had sprung a new confidence in the population of rural Ireland and emigration to America and Australia was taking its toll on rural youth; the Irish countryside was no longer a ready recruiting ground for men to carry the burden of imperial military ambition.

With the resurgence of Home Rule politics in Ireland after Parnell, Sir Timothy was a close personal friend of John Redmond, and a patron of the Irish Volunteers. His support for Home Rule was tempered by strong personal opposition to a Gaelic-dominated Home Rule Irish government and to any attempt to break the British connection – a political confusion not unknown in the Ireland of today.

After the 1916 rebellion, the weight of Irish political opinion lay with Sinn Fein. John Redmond and Sir Timothy O’Brien fell from favour for supporting Irish involvement in the British war effort in the First World War. The Irish Nationalist Party ceased to be a force in Irish politics and Sir Timothy disappeared from public life. During the War of Independence, Sir Timothy spent his time in London where he roundly condemned ‘the Irish rebels‘ in the British press. When self-rule for Southern Ireland was inevitable he was an outspoken advocate of separate Loyalist government for Northern Ireland.

Lohort castle had been sold to Eustace & Company Ltd of Cork in 1917. The castle remained unoccupied and, due to its overview of the surrounding countryside, was in regular use as an observation post by British Army patrols from Mallow Barracks throughout the War of Independence. On the night of 7th of July 1921, the castle was set on fire by the local Volunteers. The fire smouldered and burned for two full months.

After the signing of the Treaty in 1922, Sir Timothy declined to reconcile himself to life under Irish self-government. He went to London were he died, broke and in obscurity, in 1928. To Irish people, from a perspective of over 70 years of successful independent nationhood, Sir Timothy O’Brien emerges as a man of no historical stature. He was fully pledged to an Establishment class that ruled ‘the Empire on which the sun never sets’. He lived to see that great empire crumble and his class and political cohort in Ireland pushed aside and replaced by Irish national resurgence. But he was an outstanding international sportsman and we Irish love our sportsmen (and women!). He was at the centre of a famous slander case, and he involved himself at some level in all the stirring events through which he lived. His time at Lohort is now remembered only for two things

- He brought the first motor car to this part of County Cork, and

- A famous England batsman,he was bowled for a duck by a Castlemagner man!